A nanoscale window to the biological world

If the key to winning battles is indeed knowing both your enemy and yourself, then scientists are now well on their way toward becoming the Sun Tzus of medicine by taking a giant step toward a priceless advantage – the ability to see the soldiers in action on the battlefield.

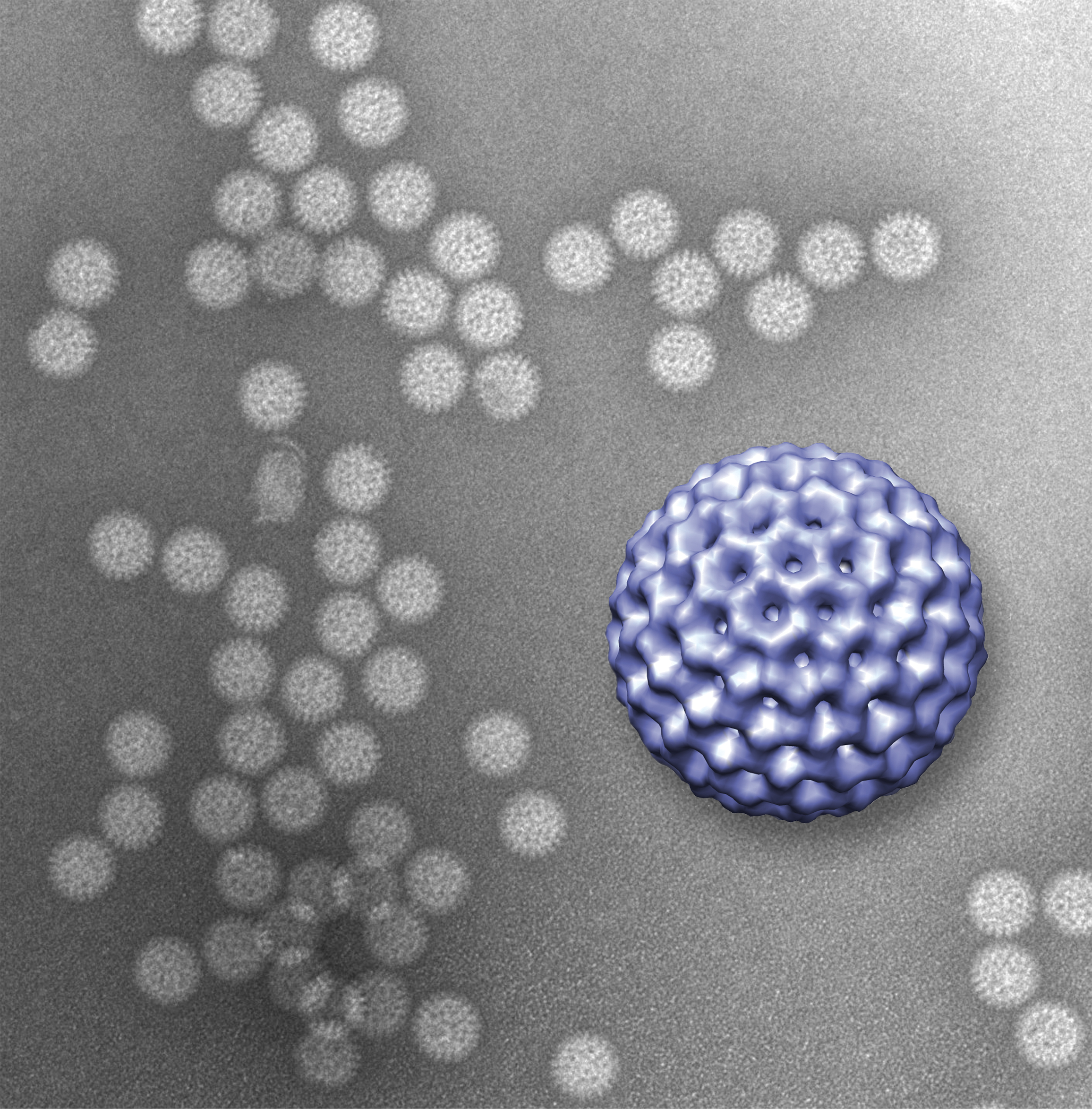

Investigators at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute have invented a way to directly image biological structures at their most fundamental level and in their natural habitats. The technique is a major advancement toward the ultimate goal of imaging biological processes in action at the atomic level.

“It’s sort of like the difference between seeing Han Solo frozen in carbonite and watching him walk around blasting stormtroopers,” said Deborah Kelly, an assistant professor at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute and a lead author on the paper describing the first successful test of the new technique. “Seeing viruses, for example, in action in their natural environment is invaluable.”

The technique involves taking two silicon-nitride microchips with windows etched in their centers and pressing them together until only a 150-nanometer space between them remains. The researchers then fill this pocket with a liquid resembling the natural environment of the biological structure to be imaged, creating a microfluidic chamber. Then, because free-floating structures yield images with poor resolution, the researchers coat the microchip’s interior surface with a layer of natural biological tethers, such as antibodies, which naturally grab onto a virus and hold it in place.

In the study, recently published in Lab on a Chip, Kelly joined Sarah McDonald, also an assistant professor at the research institute, to prove that the technique works. McDonald provided a pure sample of rotavirus double-layered particles for the study.

“What’s missing in the field of structural biology right now is dynamics – how things move in time,” said McDonald. “Debbie is developing technologies to bridge that gap, because that’s clearly the next big breakthrough that structural biology needs.”

Rotavirus is the most common cause of severe diarrhea among infants and children. By the age of five, nearly every child in the world has been infected at least once. And although the disease tends to be easily managed in the developed world, in developing countries rotavirus kills more than 450,000 children a year.

At the second step in the pathogen’s life cycle, rotavirus sheds its outer layer, which allows it to enter a cell, and becomes what is called a double-layered particle. Once its second layer is exposed, the virus is ready to begin using the cell’s own infrastructure to produce more viruses. It was the viral structure at this stage that the researchers imaged in the new study.

Kelly and McDonald coated the interior window of the microchip with antibodies to the virus. The antibodies, in turn, latched onto the rotaviruses that were injected into the microfluidic chamber and held them in place. The researchers then used a transmission electron microscope to image the prepared slide.

The technique worked perfectly.

The experiment gave results that resembled those achieved using traditional freezing methods to prepare rotavirus for electron microscopy, proving that the new technique can deliver accurate results.

“It’s the first time scientists have imaged anything on this scale in liquid,” said Kelly.

The next step is to continue to develop the technique with an eye toward imaging biological structures dynamically in action. Specifically, McDonald is looking to understand how rotavirus assembles, so as to better know and develop tools to combat this particular enemy of children’s health.

The researchers said their ongoing collaboration is an example of the cross-disciplinary work that is becoming a hallmark of the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute.

“It’s an ideal collaboration because Sarah provides a phenomenal model system by which we can develop new technologies to move the field of microstructural biology forward,” said Kelly.

“It’s very win-win,” McDonald added. “While the virus is a great tool for Debbie to develop her techniques, her technology is critical for allowing me to understand how this deadly virus assembles and changes dynamically over time.”

The paper “Visualizing viral assemblies in a nanoscale biosphere” was published online this month and will appear in a 2013 edition of Lab on a Chip. The authors are Brian Gilmore, a research associate at the VTC Research Institute; Shannon Showalter, a research assistant at the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute; Madeline Dukes, an applications scientist at Protochips; Justin Tanner, a postdoctoral associate at the research institute; Andrew Demmert, a student at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine; McDonald, who, in addition to her position at the research institute, is an assistant professor of biomedical sciences and pathobiology in the Virginia–Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine; and Kelly, who, in addition to her position at the research institute, is an assistant professor of biological sciences in Virginia Tech’s College of Science.

Related Links

- Fingers on the pulse: Neuroscientists prove ultrasound can be tweaked to stimulate different sensations

- Suspicion resides in two regions of our brains, with our baseline level of distrust distinct from our inborn lie detector

- Jamie Tyler receives prestigious McKnight Technological Innovations in Neuroscience Award