Associate professor helps lay groundwork for pending study linking deli-cut meats to deadly listeriosis infection

A professor with the College of Engineering at Virginia Tech helped build the computer model behind a draft analysis by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) that could link deli counter sliced meats to a deadly Listeria monocytogenes pathogen.

Now under peer review and not finalized, the federal comparative risk assessment indicates that 83 percent of all annual listeriosis illnesses and deaths blamed on deli meats are associated with products sliced at retail. The remaining percentage is derived from meats found in prepackaged vacuum-sealed containers.

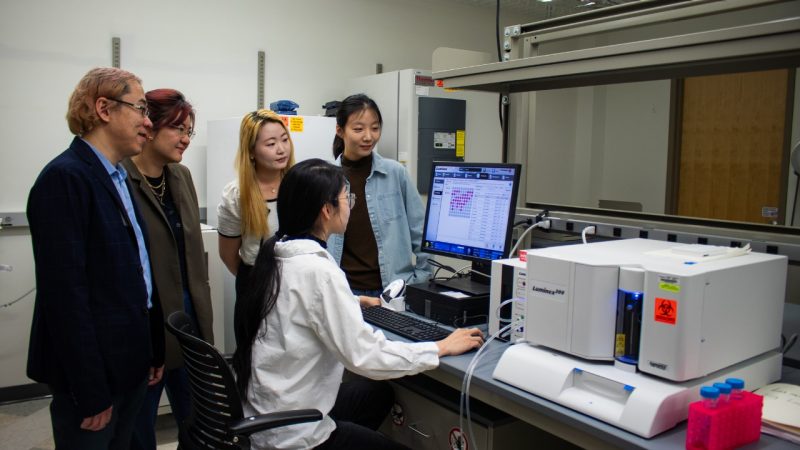

Daniel Gallagher, an associate professor with Virginia Tech’s Via Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, helped write the computer modeling code for the new comparative risk assessment by the Food Safety Inspection Service (FSIS), an agency under the USDA. Gallagher based his work on previous efforts tracking the origin and spread of food bourne illnesses by computer under the USDA in 2003 and 2006.

Listeriosis is an infection caused by eating food contaminated with the bacterium Listeria monocytogenes. It can cause vomiting, diarrhea, fever-like symptoms, muscle aches, and convulsions. Infections during pregnancy have been linked to miscarriages, stillbirths, premature delivery, or infection of the child. The elderly and those with weakened immune systems also are at particular risk if infected.

Approximately 500 Americans die each year from Listeria monocytogenes, according to a 2003 federal study. Of the roughly 2,500 illnesses reported annually, 1,600 were linked to deli meats, the study indicated.

In a previous study for federal food safety regulators, Gallagher built a computer code that originally linked a large percentage of all Listeria cases to all deli meats, pre-sliced and packaged, or not. Because of the findings, regulators were able to instigate new industry rules including that most prepackaged deli meats either be steam pasteurized or have chemical additives after cooking to minimize bacteria growth.

The meat-processing industry fell in line, but the efforts did not drop the death rate of Americans by listeriosis. “We had predicted we’d be saving 100 lives per year,” Gallagher said. So the FSIS and Gallagher again went back to the plant-store-home model for deli meats. They found that deli meat sliced at the retail counter may carry a greater risk of higher bacteria levels compared to pre-sliced and vacuum-sealed packaged meats. “By a factor of four to five,” Gallagher said. “If five people died of Listeria, four died from the deli counter meat, and one died from the vacuum sealed meat.”

The exact cause behind the spread of the Listeria monocytogenes bacterium is not yet known. Gallagher now will help FSIS regulators create a computer model that will track contamination and how deli meats are handled, how often slicers and serving areas are cleaned between cuts, and if the problem lies at the home with shoppers keeping meats past the food’s expiration date. The study won’t include restaurants and deli shops, where it is believed that food is served to customers in short periods of time before bacteria can exponentially grow.

Gallagher served as the principle architect of the agency’s comparative risk assessment model, says Carl Schroeder, deputy director of Risk Assessment and Residue Division, part of FSIS. Gallagher’s work has and will have a big impact on the work done by FSIS to improve food safety standards, Schroeder added.

An environmental engineer by training, Gallagher normally focuses his computer modeling efforts on the U.S. water infrastructure. He has worked on computer projects on water quality and distribution by tracking customer complaints, seen as an early warning sign of a failing or leaking pipes. He earned his undergraduate degree in civil engineering in 1979 and his master’s in environmental engineering in 1981, both from Drexel University, and a doctoral degree in environmental engineering from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill in 1986.

See related story: