Researcher shows plumbing materials may taint your tap water

Metal or plastic? Water pipes, that is. When it comes to drinking water, the choice is important because it will help determine whether your water will be free of foreign smells.

The human nose is pretty sensitive, designed by nature to pick up offensive odors that might signal that a food or beverage is acceptable for consumption.

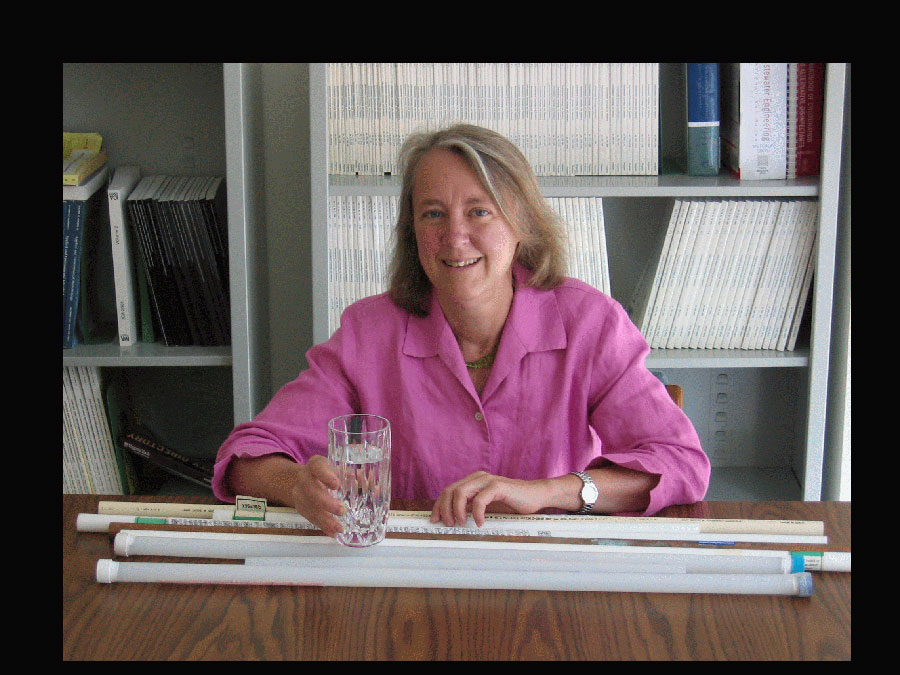

Andrea Dietrich, professor of civil and environmental engineering at Virginia Tech, conducts research focused on determining which pipes are to blame for funny tasting tap water. Her research group studies how different plumbing materials affect the odor and taste of drinking water. Uniquely, she includes a panel of trained human “testers” to assess what she describes as “water aesthetics.”

Her goal is to have an aesthetic assessment included as one of the tools used to evaluate materials in contact with water. Existing assessments only evaluate the chemical and biological safety of water, but consumers want water that is palatable, as well as safe. According to Dietrich, “Other food and beverage manufacturers assess “taints” from packaging to their products, so pipe manufacturers should also do this because water pipes are a type of food packaging. It is difficult for water utilities to control off-flavors that enter water from piping because this occurs after the water leaves the treatment facility.”

Plastic is increasingly used nowadays, however different polymers seem to either interact with the chemicals used to disinfect the water, or to trap unpleasant odors that form during the extrusion process; even the surface lining of the pipe itself can oxidize and infuse tap water with a characteristic smell.

The National Science Foundation sponsored Dietrich’s research project. She and her research team treated purified water with the usual disinfectants found in tap water. They let the samples sit in various types of polymer pipes for three days. Then they asked a commissioned panel to evaluate the water as they would a glass of wine.

Among the materials tested, chlorinated polyvinyl chloride (cPVC) ranked as the polymer least likely to give drinking water an offensive odor. According to Dietrich’s final report, “Results indicate that copper pipe consumed nearly all the residual disinfectants […] results for the polymer materials indicated that cPVC imparted the fewest organic compounds to the water, consumed the least amount of disinfectants, and produced no noticeable odors. All other polymer materials imparted distinct odors and organic chemicals to water and consumed residual disinfectant.”

Lowest amount doesn’t mean nonexistent, though. An aftertaste of plastic was detected in the cPVC sample, but according to Dietrich, it disappeared with continuous use of the pipe for a couple of months, depending on frequency of usage.

The research tested only pipe materials. Fittings and chemicals that are used to install pipes may also have odors. This problem has been noted for the glues used to seal sections of PVC pipe. Dietrich is an active faculty participant in teaching, research, and outreach at Virginia Tech since her arrival in Blacksburg in1988. She has taught in the Commonwealth Graduate Engineering Program since 1989. She also acts as consultant for the identification and monitoring of tastes and odors in drinking water.

Dietrich earned a bachelor’s degree in chemistry and biology from Boston College, a master’s in environmental science and engineering from Drexel University, and an environmental science and engineering doctorate from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Her research interests include water quality, water treatment, sensory analysis for taste and odor compounds, understanding the fate and transport of organic and inorganic chemicals, and environmental analytical chemistry.